For language and literacy, this means we can use vocabulary in a new essay that we write. When we learn, we build upon past learning. Graphic novels and comic books provide one avenue for making inferences with words and pictures, but this is a developed skill of posing questions, thinking about the decisions authors make in storytelling, and then dealing with the problem-solving steps of carrying authorly work into students' own writing. In literacy instruction, the ‘problems' we encounter are often found in the choices authors make in conveying meaning, sometimes relying on us to make inferences based on the breadcrumbs they provide. Part of being an effective educator in any content area is knowing the value of a powerful and well-placed question. This is a progressive effort in written language, but also another reminder that our classrooms cannot be silent at all times. ‘Can you say that again?', ‘Can you tell us more?' Teachers can consider encouraging ways that are inviting and positive to allow students more opportunities to think and share. Thinking and communicating with precision This is yet another place where revision is powerful work.

We do not envision that enactment of precision, but rather see a continuum of getting better, more in line with a growth mindset approach. What's that word again? In the world of Lois Lowry's dystopian novel The Giver, students are swatted when they speak imprecisely. This is invisible work, and it is complicated – but one way that teachers can model metacognition is in reading aloud and holding discussions. How many of us have reached the end of a passage and realised we weren't attending to meaning at all, but were distracted by other thoughts? Within the practice of metacognition as a Habit of Mind, we see an essential reading skill. This flexible response is especially important as the second language knowledge a student brings can be regarded as a strength to maximise, rather than a deficit to undermine. These reading experiences build on a framework of strength rather than deficit allows teachers to flexibly respond to help students grow. We become better readers as we move through experiences of success, starting with books that we find comfort in, and moving to more complex reading. This is no less true when it comes to considering the resources students have in terms of their digital literacy, as well as in traditional print literacy. If there is nothing else that being an educator has taught us through the COVID-19 pandemic, it is that we must take a flexible approach to student learning. In our literacy classrooms, we envision room for healthy discussions and active work that takes place in the whole group, as well as in small groups. It is through dialogue that we become better learners and thinkers. Literacy classrooms are not silent places, and are not spaces for stories to be silenced, either. Listening to others with understanding and empathy We can also recognise that reader identity is shaped over time. There is always more story to be told, and we find our own challenge in recognising the power of all narratives and the importance of the work that authors do. In practice, this ‘jump' may sound like: ‘This is not the right book for me' or ‘I know all of that story already', or it may even be ‘I'm just not a reader'.

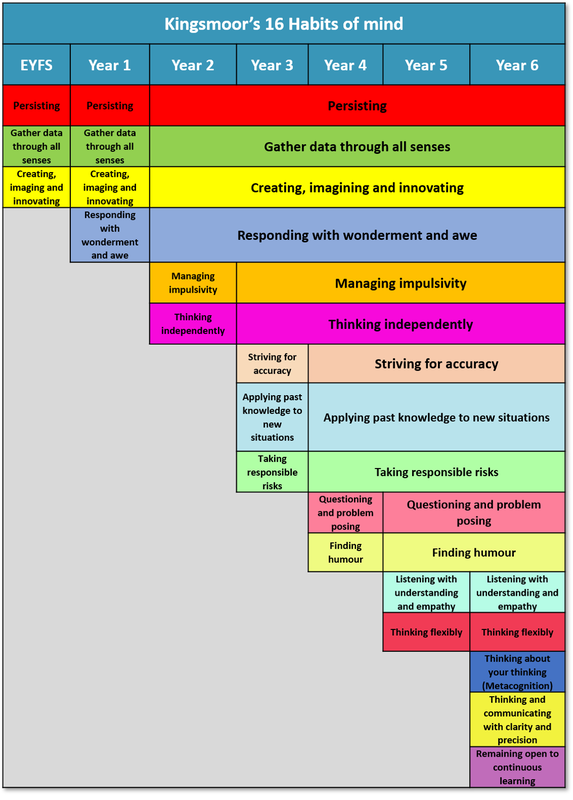

Rather than take the standard classroom approach to managing impulsivity as a behaviour concern, we see the potential in this Habit of Mind for resisting the urge to jump to simplistic conclusions. As teachers, we can normalise progress by discussing our own experiences of persistence and by being transparent about the ways we have learned and grown. After all, no writer was born forming perfect letters and plots. Our classrooms are spaces of encouragement and revision as we improve our reading, writing, and speaking. Finding the right tools to do that work, through reading and using words and pictures, is a powerful echo to the idea of persisting. The following discussion addresses each of the 16 habits and ways that we can use these with students as they learn about literacy and language.Ī key ingredient in the literacy classroom is a commitment to telling one's story. One of us has already written about the Habits of Mind in a variety of ways, including in language learning (Mason, 2019), but here we turn our attention as a united effort to the field of literacy. By applying them in the areas of English and literacy, we invite our students to become fully engaged in their learning in a way they may have never imagined. The Habits of Mind, developed by Arthur L Costa and Bena Kallick, focus on 16 habits or dispositions that help with life's challenges and education (Costa & Kallick, 2008 Costa & Kallick, 2009). Building a classroom where reading, writing and speaking are valued, and where stories are shared, is hardly simple work.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)